Susan Sontag once wrote that “people who favour women working for their liberation in concert with men tacitly deny the realities of women’s oppression.”

Discourse about feminism — especially since the advent of the #MeToo movement in — has grossly overemphasised the point that men can, and should be feminists too. Emma Watson’s HeForShe campaign, launched in 2014, is another trademark of that era. My point in this essay is not that men can’t, or shouldn’t be feminists, it is that the Women’s Movement should predominantly be a women’s-only space. Because it is only through cultivating spaces where our voices, thoughts, strategies, and leadership are as far removed from patriarchal society as possible that a movement radical enough to push for our liberation without hindrance can arise.

The oppression of women, historically and presently, remains one of the most intimate forms of oppression. It is enacted not just through state structures or capital, but in family kitchens, on dates, during sex, and through the casual cruelties of daily life. Patriarchy is not some abstract system—it is a man who interrupts you when you speak, a boyfriend who weaponises feminist politics against you in a fight, a male “ally” who expects praise for doing just about anything.

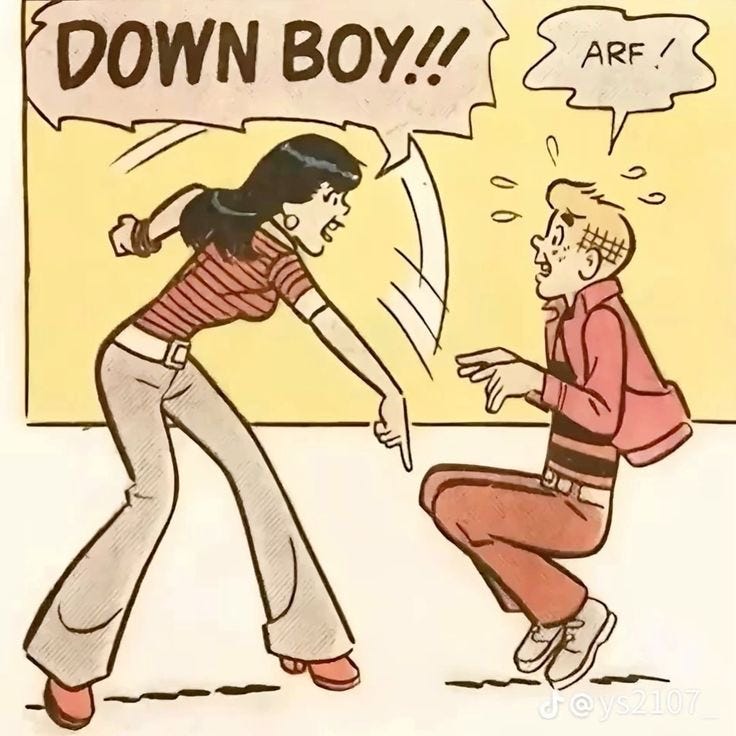

This is why it is not merely impractical, but ideologically compromising, to centre men in the Women’s Movement. Male inclusion often comes at the cost of women’s comfort, clarity, and political focus. The presence of men—however “feminist” they might be—introduces a subtle pressure to soothe egos, temper our demands, or reward their participation. When men are present—even the good ones, even the ones who listen—we unconsciously shrink. We measure our words. We preempt defensiveness. We centre their feelings, their reputations, their desire to be seen as “good guys.” And in doing so, we betray ourselves. Because such pressures already exist and are prevalent in our day-to-day lives.

When oppression is this intimate, the work of unlearning it cannot be done under the male gaze. We need women’s-only spaces not as a luxury or a separatist indulgence, but as a political necessity. These are the only spaces where we can lower the defences we didn’t even know we were holding up. Spaces where we can speak without translating, share without softening, rage without apologising.

Most importantly, women-only spaces offer the rare opportunity to imagine. To dream outside the boundaries of male approval and build visions of liberation not shaped by what men will tolerate, but by what women truly need.

So, in spaces that are fully ours, something electric can take shape. We begin to name things we didn’t have words for. We laugh in recognition, connect dots between the personal and the political. We get braver. We start to realise just how much we’ve been tolerating, and how little of it we actually have to.

I read this one book when I was 14, Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race, Reni Eddo-Lodge. The author powerfully laments the exhaustion of explaining racism to white people, of constantly making the case for one’s own oppression to those who benefit from it. She argues that when the oppressed must always engage the oppressor, even in movements for justice, the emotional and intellectual labour falls disproportionately on the marginalised. Anti-racist movements, like feminist ones, have historically been co-opted, diluted, or derailed when centred around making white people feel comfortable enough to participate. Eddo-Lodge’s decision to disengage was not about giving up on anti-racism—it was about reclaiming the energy, focus, and clarity that comes when Black people organise among themselves. The same principle holds true for women. Liberation is not something that can be negotiated into existence with those who uphold the very systems we seek to destroy. Like anti-racist movements that insist on the authority of the oppressed to speak, lead, and imagine without white approval, the Women’s Movement must fiercely protect its right to centre women—without apology, without dilution, and without male validation.

There is a concerning lack of discourse on the necessity of the exclusion of men from the Women's Liberation Movement. Perhaps because it still seems immoral to exclude our beloved, earnest fathers, brothers, and boyfriends — especially since and perhaps, at least partially, due to the “Not All Men” discourse that took us by storm back in 2020.

I digress, a study from the Vancouver Rape Relief & Women’s Shelter, asserts, women-only spaces are essential for cultivating feminist autonomy and resisting the dilution of radical political agendas. Patricia McFadden, in this study, rather intelligently draws attention to just how many spaces women have historically been and still are (especially in the global south) excluded from.

There needs to be more discourse on feminist autonomy in this sense, especially as a natural development from the booming online discourse around the male gaze, corny male feminists on Hinge, and the safety and importance of female friendships. Circling back to Sontag, a lot of her work centres around how the patriarchy monopolises women’s cognitive, imaginative space too. It limits just how liberated we are able to envision ourselves, even in the comfort of sitting alone in a room of one’s own. I can only imagine how much larger this hinderance becomes if a man is sitting there with you.

Radical visions are fragile in their earliest stages—they need an incubator as free from our oppressors as possible to grow. This freedom will only inevitably arise through exclusion: the exclusion of men not from feminism, but from the Women’s Movement. Women-only spaces can thus become incubators of radical political strategies which truly challenge our system and enact change — without even the kindest and most well-meaning of our oppressors present to dilute our discourse.

Super interesting read - I find it so refreshing to see “women’s spaces” described as a place of organising power. In the current political climate of anti-trans rhetoric parading as feminist, the term is so often used to suggest an innate and inherent weakness in cis women that requires sheltering, and I worry there’s a wave of men claiming to want to “protect women’s spaces” as a guise for being paternalistic. When a woman’s space is a public bathroom they’ll sound off about protecting it, but when a woman’s space is a forum in a bookshop for sharing information, or a literary journal that doesn’t prioritise men after centuries of literature doing the same, suddenly they’re being excluded.